There are 14 spots with specially chosen poetic passages waiting to be discovered in the garden! You'll find examples from Spain to SE Asia originally written in Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Urdu, Hindi and Malay.

Close this screen, go to a spot on the map and tap on a marker.

5 stopsTIME NEEDED

1 stop ~ 5 min.

All stops ~ 30 min.

POEM 1

@ the Woodland Bagh Entry

To promenade alone in the garden

I am not the one,

Even were it Heaven I would refuse it.

Lakhnavi, Ghalib (Lucknow, India, writ. 1855) and Abdullah Bilgrami (Lucknow, writ. 1871). Excerpt from The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. 2007. (Original in Urdu.)

Why Here?

The Woodland Bagh entrance to the Aga Khan Garden is a place to consider whether gardens are best enjoyed alone or with company. The writer stresses the importance of companionship, revealing that gardens were more often visited with friends and family than just by oneself. They were social places to enjoy the company of others.

About this passage

This poem is from a 19th C Urdu version of the The Adventures of Amir Hamza. It is recited by the trickster Amar Ayyar to the general of his beloved companion, Amir Hamza, in order to con him out of some gold. Ayyar pretends to be dead, posing as the Angel of Death. He informs the general that Ayyar has refused to enter the garden of paradise without the general, as the passage states. Fearful of accompany the angel to his death, the general offers the false angel Ayyar a chest of gold in exchange for his life.

The episode is one of many fantastical adventures of Amir Hamza, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, that have been retold across the Islamic world since the 7th century. As the scholar Hamid Dabashi puts it, the story "speaks the imagination of peoples and worlds extended all the way from North Africa to Central Asia, from South Asia to China" (Lakhnavi and Bilgrami, 226).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Bilgrami, Abdullah, and Ghalib Lakhnavi. “Excerpt.” In The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Complete and Unabridged Translation, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi, 226. New York: Modern Library, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/883417767.

- Pritchett, Frances. “The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dastan-e-Amir Hamzah.” India International Centre Quarterly 19, no. 3 (1992): 27–47. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6015492798.

- Keshani, Hussein. Woodland Bagh - Entry. Edmonton, 2018. Digital Image.

- Turku, Nomads of the Silk Road. Lesgi. Vol. Nomads of the Silk Road, 2000. https://archive.org/details/Nomads_of_the_Silk_Road_Golden_Festival_2012-11076/Turku_-_03_-_Lesgi.mp3#

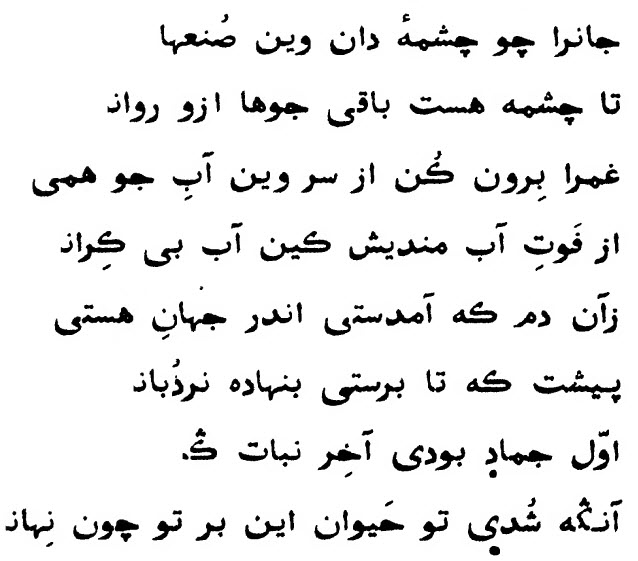

POEM 1

@ the Woodland Bagh Pool

Conceive the Soul as a fountain,

and these created things as rivers:

While the fountain flows,

the rivers run from it.

Put grief out of your head and keep quaffing this river water;

Do not think of the water failing;

for this water is without end

From the moment you came into the world of being,

A ladder was placed before you that you might escape.

First you were mineral, later you turned plant,

Then you became animal: how should this be a secret to you?

Rumi (Konya, Turkey, d. 1273). "XII." In Divani Shamsi Tabriz. Translated by R. A. Nicholson. 1898. (Original in Farsi.)

Why Here?

At the Woodland Bagh pool, one finds water, plants, minerals (granite), and animals, the spectrum of creation mentioned in the poem. The poem's use of water as a spiritual metaphor suits the quiet ambiance of this court well.

Original Text

About this passage

In this passage, the poet Rumi uses flowing water and its source as a metaphor for the endless rejuvenation of creation by the Divine.

Mawlana Rumi was born in Central Asia and died in Konya, Turkey in 1273. Trained as theologian and legal scholar, he distinguished himself as a mystical poet. The excerpt is from a collection of over 40,000 verses called either the Diwan-i Kabir (The Great Collection) or the Diwan-i Shams-i Tabrizi (The Collection of Shams of Tabriz). Rumi composed these works following the spiritual transformation he underwent after meeting and training with his beloved teacher Shams of Tabriz, who sadly disappeared.

Rumi's works ranged from the contemplative to the erotic and were written mostly in Persian but also Arabic, Turkish and Greek, an indication of the multicultural environment in which he lived.

His actual name was Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī or Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Rumi. Rumi referred to the place he was from - Anatolia (i.e. modern Turkey) - which was known as Rome because it was formerly the seat of the Eastern Roman (i.e. Byzantine) empire (Nicholson, xv-li).

Today, his works have been translated into many languages, and he is one of the most popular poets in the English language.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Ǧalāl-ad-Dīn Rūmī. “XII.” In Selected Poems from the Dīvān-i Shams-i Tabrīz: Ed. and Transl. with an Introd., Notes and App., translated by Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, xv-li; 47. Cambridge: Univ. Press, 1898. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.52959/page/n3. Farsi and English.

- Wallace, Jeff. Aga Khan Garden - Reflective granite basin in the Woodland Bagh. 2018. https://archnet.org/print/preview/mediacontents=134691&views=i

- Turku, Nomads of the Silk Road. Lesgi. Vol. Nomads of the Silk Road, 2000. freemusicarchive.org. http://freemusicarchive.org/music/Turku_Nomads_of_the_Silk_Road/Nomads_of_the_Silk_Road/10_Lesgi.

POEM 1

@ the Woodland Bagh Seep Fountain and Chowk

There is blissful rain in Susamana [the joyous mind];

there lives the Pure, Formless.

There is no flute yet there is music;

there is no sun yet there is light.

There is no river yet there is flow;

there is no company, yet there is an assembly.

Pir Shams Sabzwari? (Sabzawar, Afghanistan/Multan, Pakistan, d. 675/1276). Excerpt from Bhrama Prakash (Divine Light). Translated by Shiraz Pardhan. 1982. (Original in Hindi)

Why Here?

The downward water sprays in the Chowk are like rain, a focal point in the hymn. As in the text, the source of the water is not obvious, though we know there must be a point of origin.

Original Text (Transliteration)

Zarmar varse sukhamana meha;

Rahet nirinjan jahan van deha.

Nahi tur jahan hai bi tura,

Nahi sur jahan hai bi sura.

Nahi gang jahan hal bi ganga;

Nahi sang tahan hal bi sanga.

About this passage

This excerpt describes what it is like to achieve a peaceful and joyous state of mind. The passage belongs to a lengthy proselytic Ismaili Muslim hymn (granth) Bhrama Prakash in which concepts of meditation, spiritual progression and the Divine common to Shia Ismaili Islamic and Vedic beliefs are sung about using Ancient Indian religious melodies (Pradhan).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Pradhan, Shiraz. “The Inward Odyssey.” Ilm, Volume 8, Number 1, November 1982. (Published by the Shia Imami Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Board for the United Kingdom.)

- Dialog Design. Detail of Chowk Spray Fountain. 2018. Digital photograph.

- Ustad Abdul Karim Khan. Jamuna Ke Tira Kanha - Bhairavi Thumri (Adha Tal). India: Columbia, 1934. freemusicarchive.org. http://freemusicarchive.org/music/Ustad_Abdul_Karim_Khan_-_Bhairavi_thumri_adha_tal/.

POEM 1

@ the Woodland Bagh Amphitheatre

As the Shadow of God approached the Garden

The blossoms in ecstasy bloomed out of scope.

Imam Baksh Nasikh (Lucknow, India, d. 1838). In The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. 2007. (Original in Urdu.)

Why Here?

The shadows of surrounding trees are often cast onto the Amphitheatre and shadow is an important image conjured by the poem. Just beyond the amphitheatre lies the Chahar Bagh, which, like the garden in the poem, lies out of view and is filled with flowers in the summer.

About this passage

This poem describes how flowers in a royal garden - in anticipation of the arrival of an emperor - blossom . Authority and power are associated with fertility and fecundity. The poem's author Imam Baksh Nasikh was a leading Urdu poet in the early 19th century, who was fond of both eating and wrestling (Schimmel, 196)! The phrase "Shadow of God" was a famous title that was often used by rulers across the Islamic world who saw themselves as God's representative on earth.

The poem is cited in the Adventures of Hamza to lend colour to a story being told in which an emperor approaches a wondrous garden called Bagh-e Bedad. The servant Alqash has built the garden to impress the emperor and earn his favour but things will not turn out well (Lakhnavi and Bilgrami, 14).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Imam Baksh Nasikh. “Excerpt.” In The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Complete and Unabridged Translation, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. New York: Modern Library, 2007. p. 14. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/883417767.

- Schimmel, Annemarie. “Urdu Literature from 1700 to 1850.” In Classical Urdu Literature From The Beginning To Iqbal. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1975. pp. 196–97. http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.202745.

- Wallace, Jeff. Aga Khan Garden - Amphitheatre. 2018. https://archnet.org/sites/16792/media_contents/134700.

- Gnawledge, and Uzman Almerabet. El Arte de Escuchar. Mp3. Vol. Granada Doaba. Spain: Gnawledge Records, 2009. freemusicarchive.org. http://freemusicarchive.org/music/Gnawledge/Granada_Doaba/14_El_Arte_de_Escuchar.

POEM 1

@ the SE Talar

Come and drink with me, now that the garden wears,

A gown of flowers woven by the rain,

Now the veil of the sun is golden

And the green skirt of the earth pearled with dew

In this pavilion which is like the firmament in which

The face of my beloved like the moon shines.

The stream is like the Milky Way flanked by The guests brilliant stars.

Ali ibn Ahmad (Valencia, Spain, 11th C.) Translated by Unknown. (Original in Arabic.)

Why Here?

Garden pavilions like this one, which is called the Talar, were not only favourite places to eat and drink together, but also survey the beauty of nature. The Talar is a great place to observe to garden in its full splendour as the poem's narrator does. For the poet, the garden pavilion reminds him of the radiant moon and his beloved. As you stand here, does anyone special come to mind?

About this passage

Poems about gardens (rawdiyyat), and flowers (nawriyyat), were popular types of poetry in medieval Muslim Spain - al-Andalus - where this poem was written (Bermejo and García Sanchez, 63-4). This passage celebrates the the royal garden estates called Almunia belonging to the Muslim ruler Al-Mansur in Valencia, Spain and reflects how gardens in the courts of Medieval Spain were sites of pleasure and romance.

Partly modelled after quarters in Cordoba and the Syrian countryside, the Almunia of Valencia was home to reigning princes but seems to have become a public park when the poem was written (García Sanchez, 208; Bargebuhr, 243; Sanz, 24-25).

Medieval Spain was a place of vibrant cross-cultural encounters, sometimes peaceful and sometimes contentious, between Europeans, Arabs and North Africans and between Muslims, Jews and Christians. Arabic, Hebrew, and Castillian poetry shared themes and genres, while Christian kings lived in Muslim rulers' palaces, gardens and mosques built upon Roman and Middle Eastern precedents.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Ali bin Ahmad (Valencia, Spain, 11th C), Inés Eléxpuru, and Margarita Serrano. “Excerpt.” In Al-Andalus, Culinary Magic and Seduction, translated by Unknown. Madrid: Islamic Culture Foundation, 1991. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/434867421.

- Ali ibn Ahmad (Valencia, Spain, 11th C), and Frederick P Bargebuhr. “Excerpt.” In The Alhambra: a cycle of studies on the eleventh century in Moorish Spain, translated by Frederick P Bargebuhr. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/644952512.

- Bargebuhr, Frederick P. “A. Introduction - Nature Poetry of the Eleventh Century.” In The Alhambra: a cycle of studies on the eleventh century in Moorish Spain, 243. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/644952512.

- Bermejo, J. Esteban Hernández, and Expiración García Sánchez. “Tulips: An Ornamental Crop in the Andalusian Middle Ages.” Econbota Economic Botany 63, no. 1 (2009): 60–66. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7025658382.

- García Sánchez, Expiraciòn. “Utility and Aesthetics in the Gardens of Al-Andalus: Species with Multiple Uses.” Health and Healing from the Medieval Garden. 2008, 205–27. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5894455808.

- Pérès, Henri (1890-1983) Auteur du texte, and Institut d’études orientales (Alger) Auteur du texte. La Poésie Andalouse En Arabe Classique Au XIe Siècle , Ses Aspects Généraux, Ses Principaux Thèmes et Sa Valeur Documentaire. 2e Édition... Par Henri Pérès,..., 1953. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3338413m.

- Sanz, Vicente Coscollá. La Valencia musulmana. Carena Editors, S.l., 2003.

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - Talar. 2018.

- Ensemble TAVOIS. Xorazmcha, 2008. www.classicmusic.uz/. http://www.classicmusic.uz/music/Tavois/www.classicmusic.uz_Tavois_Xorazmcha.mp3.

POEM 2

Come, spend a night in the country with me,

my friend (you whom the stars above

would gladly call their friend),

for winter’s finally over. Listen

to the chatter of the doves and swallows!

We’ll lounge beneath the pomegranates,

palm trees, apple trees,

under every lovely, leafy thing,

and walk among the vines,

enjoy the splendid faces we will see,

in a lofty palace built of noble stones.

Solomon Ibn Gabirol (Valencia, Spain, d. c. 1058). “Excerpt from The Palace and the Garden.” Translated by Raymond P Scheindlin. 2006. (Original in Hebrew.)

About this passage

Ibn Gabirol was one of the most famous Hebrew poets of Medieval Spain. Born in Malaga to a Jewish family that had fled Cordoba, Ibn Gabirol became well-versed in the forms and motifs of Arabic literature, knowledge which he used to help lead the revival of Hebrew as an intellectual and literary language (Bargebuhr).

The poem "The Palace and the Garden" is one of Ibn Gabirol's most famous Hebrew works, modelled after the Arabic panegyric and garden poem (rawdiyyat) genres. The poet invites a friend in spring to visit a patron's wondrous garden and then the adjoining palace. They journey from outside to inside and outside again, where animals bicker and and the natural becomes blurred with the artificial (Scheindlin, 34).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Solomon Ibn Gabirol (Valencia, Spain, d. c. 1058). “Excerpt from The Palace and the Garden.” In The Literature of Al-Andalus, edited by María Rosa Menocal, Michael Anthony Sells, and Raymond P Scheindlin, translated by Raymond P Scheindlin, 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Bargebuhr, Frederick P. “Ibn Gabirol.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., May 11, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ibn-Gabirol.

POEM 1

@ the NW Talar

By virtue of Your Highness's blessings and prestige,

your [servant] has built a garden full of multitudinous flowers and fruit trees.

A host of rare plants has been collected at great expense,

and choice landscapists, past masters of the art,

have been employed to tend to them.

Lakhnavi, Ghalib (Lucknow, India, writ. 1855) and Abdullah Bilgrami (Lucknow, writ. 1871). Excerpt from The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. 2007. (Original in Urdu.)

Why Here?

From the elevated height of the Talar, much of the the garden can be surveyed. Like the garden in the passage, the Aga Khan Garden is filled with flowers and fruit trees and has been created by talented landscape designers, construction workers and horticulturists.

The reference to rare plants is especially appropriate as botanic gardens, like the University of Alberta Botanic Garden, are filled with exotic and rare plants from all over the world.

About this passage

In the fantastical tales of Amir Hamza, a wondrous garden called the Bagh-Bedad was commissioned and designed by a man named Alqash. Upon completing his garden masterpiece, Alqash invited the emperor and staged an extraordinarily lavish reception. The passage cited was part of Alqash's invitation to the emperor.

Alqash, however, was hiding a secret. The wealth he used to build the garden was obtained after murdering a man who knew of secret treasure. Later the son of the murdered man, who was endowed with supernatural intuition, visited the garden to purchase vegetables for his mother and grew suspicious, only to be abducted by Alqash's servant.

The passage reveals much about garden design and culture in general and mid-18th-century North India in particular. Private gardens appear not only as places of conspicuous consumption to enhance social status and stage opulent events for the elite, but also as a kind of open-air grocery store from which ordinary people could obtain fresh vegetables to eat (Bilgrami and Lakhnavi, 3-25). Palace gardens, like botanical gardens, also served as repositories for exotic plants from around the world.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Bilgrami, Abdullah, and Ghalib Lakhnavi. “Excerpt.” In The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Complete and Unabridged Translation, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi, 13. New York: Modern Library, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/883417767.

- Pritchett, Frances. “The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dastan-e-Amir Hamzah.” India International Centre Quarterly 19, no. 3 (1992): 27–47. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6015492798.

- Keshani, Hussein. NW Talar - View of Chahar Bagh. Edmonton 2018. Digital Image.

- Unknown. Imperial Palace Autumn Moon 《汉宫秋月》, n.d. The Internet Chinese Music Archive The Great Empire of China. https://www.ibiblio.org/chinese-music/MP3/TD03.Imperial_Palace_Autumn_Moon.mp3.

POEM 1

@ Chahar Bagh, SW end of Nahr

I am a Muslim:

The rose is my qibla.

The stream is my prayer-rug,

the sunlight my clay tablet.

My mosque, the meadow.

I rinse my arms for prayers

along with the thrum and pulse of windows.

Through my prayers streams the moon, the refracted light of the sun.

Sohrab Sepehri (Iran, writ. 1965). Excerpt from Water's Footfall. Translated by Kazim Ali with Mohammed Jafar Mahallati. (Original in Farsi.)

Why Here?

The central stream-like water channel, called the Nahr, is coincidently oriented to the Qibla, the direction of Mecca toward which Muslims generally pray. In Edmonton, the Qibla direction is often understood to be northeast.

From here, you can also see meadow-like lawns bathed in sunlight, all elements mentioned in the passage. For the poet, the adoration of nature and belief in the Divine are deeply intertwined.

Original Text

من مسلمانم

قبله ام يك گل سرخ

جانمازم چشمه، مهرم نور

دشت سجاده من

من وضو با تپش پنجره ها مي گيرم

در نمازم جريان دارد ماه ، جريان دارد طيف

About this passage

Born in 1928, the Iranian poet Sohrab Sepehri pursued an illustrious career as an artist and poet, while holding a variety of jobs until his death in 1980. Well-travelled and a student of many spiritual and religious traditions, Sepehri's journey as poet began by learning the conventions of traditional Persian verse, eventually arriving at a more modern, cosmopolitan and accessible style that weaved together poets like Emerson and Rumi the outlooks of Zen Buddhists, Taoists, Sufis and European Romantics.

Nature and the human soul feature prominently in Sepehri's poems, ideal subjects for the discernment of the world's deeper truths. The excerpt above is from one of Sepehri's most well-known poems called Water's Footfall, an autobiographical work that wrestles with the tension between prescriptive tradition and soulless modernity. In this passage, the poet alludes to how the Quran says any place can be used to pray, while drawing together references to spirituality, Islamic ritual practice and the transcendent beauty of nature (Sarshar).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Sarshar, Houman. “SEPEHRI, Sohrab.” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online Edition, August 15, 2009. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sepehri-sohrab.

- Sepehri, Sohrab (writ. 1965). “Excerpt.” In Water’s Footfall, translated by Kazim Ali and Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, Bilingual edition. Richmond, Calif.: Omnidawn Publishing, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/759910187.

- Sepehri, Sohrab (writ. 1965). “The Water’s Footfall.” In The Water’s Footfall: Selected Poems, translated by Ismail Salami and Abbas Zahedi, 18–50 esp. 18–19. Tehran: Zabankadeh Publications, 2004.

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - Chahar Bagh SW Nahr. 2018.

- Turku, Nomads of the Silk Road. Lesgi. Vol. Nomads of the Silk Road, 2000. freemusicarchive.org. https://archive.org/details/Nomads_of_the_Silk_Road_Golden_Festival_2012-11076/Turku_-_03_-_Lesgi.mp3#.

POEM 1

@ the Chahar Bagh Diwan

The sight of [this garden] has delighted us!

Its sparkling avenues, symmetrical promenades, succulent fruits,

luscious fare, rare and curious flowers, sculpted trees,

refreshing pools, and the agreeable and blissful air,

are all very luxurious and elegant indeed.

We used to hear of its air and landscaping,

and now we have witnessed it!

A most excellent garden it is,

praise be to Allah!

Lakhnavi, Ghalib (Lucknow, India, writ. 1855) and Abdullah Bilgrami (Lucknow, writ. 1871). Excerpt from The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. 2007. (Original in Urdu.)

Why Here?

From the Diwan area, it is easy to see how symmetrical avenues define the garden, which is filled with flowers and water pools, much like the garden mentioned in the passage.

About this passage

In the The Adventures of Amir Hamza, the devious Alqash convinces the emperor to visit the luxurious garden (Bagh-e Bedad) that he built with ill-gotten wealth. Upon seeing the garden, the emperor marvels out loud at its beauty and the exotic plants it contains (Lakhnavi and Bilgrami, 18).

Throughout time and across the Islamic world, including North India, the gardens of the elite were often used to grow foreign and exotic plant species; they were in effect the botanic gardens of their time.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Bilgrami, Abdullah, and Ghalib Lakhnavi. “Excerpt.” In The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Complete and Unabridged Translation, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi, 18. New York: Modern Library, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/883417767.

- Pritchett, Frances. “The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dastan-e-Amir Hamzah.” India International Centre Quarterly 19, no. 3 (1992): 27–47. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6015492798.

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - Chahar Bagh Diwan. Edmonton, 2018. Digital Image.

- Unknown. Kemençe Sound Sample. Mp3, n.d. http://www.turkishmusicportal.org. http://www.turkishmusicportal.org/en/api/listen/klasik-turk-muzigi-kemence.

POEM 1

@ the Jilau Khana

I knocked at the door of a garden blooming like youth,

while the morning sun shone unwinking on the horizon;

The dew quivers in the daffodils' tears like lovers' tears,

The camomile blossoms break open with a smile, and the wind-flowers' cheeks redden with shame;

Fruits tremble on their branches like the breasts of maidens, slender as willow's branches.

A fresh sweet-watered brook untouched by the sun draws his silver-sword against them,

While the naked palms loom high up, a necklace of dates adorning their breasts.

Ibn al-Tazi?. (Sicily, Italy, ca. 11th C.) Excerpt from Untitled. (Original in Arabic.)

Why Here?

The passage highlights the anticipation felt upon entering a garden in bloom, or when seeking romance. Although there is no door to the garden as the poem mentions, this entrance area, which is called the Jilau Khana, is clearly marked by two metal geometric screens and is one of two principal entrances to the garden, the other being the Woodland Bagh Entry.

About this passage

This poem describes visiting a palm garden by a brook in Sicily and likens the teeth of a lover's smile to a display of chamomile blossoms, a common reference in Arabic romantic poetry. A fertile blooming garden is likened to a beautiful young woman, joining male heterosexual desire with a love of gardens (Gabrieli, 14).

Arab Muslims, like the Aghlabids and the Fatimids who were based in Tunisia, North Africa (and later the Sicilian Kalbids) ruled in southern Italy from the 9th to the 13th century. They continued to dwell there after the Norman Christian kings took over the region in the 12th century. The traces of Sicily's Arab past are perhaps best seen in its historic capital of Palermo.

Sicily was one of several Mediterranean routes for crosscultural exchange between Europe and the Islamic world in sciences, trade and culture (Scarfiotti and Lunde; Metcalfe). The Arab presence in Sicily led to the introduction of new crops (cotton, hemp, date palms, sugar cane, mulberries and citrus fruits) and technologies (eg. irrigation techniques and paper-making) that would help transform Europe.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Gabrieli, Francesco. “Arabic Poetry in Sicily.” East and West 2, no. 1 (1951): 13–16 esp. 14. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6015334683.

- Ibn al-Tazi? (d. 11th C) “Excerpt from Untitled [in Arabic Poetry in Sicily].” Translated by Francesco Gabrieli. East and West 2, no. 1 (1951): 13–16 esp. 14. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6015334683.

- Metcalfe, Alex. The Muslims of Medieval Italy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/917154802.

- Scarfiotti, Gian Luigi, and Paul Lunde. “Muslim Sicily.” Aramco World: Arab and Islamic Cultures and Connections, December 1978. http://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/197806/muslim.sicily.htm.

- Keshani, Hussein. Chahar Bagh - Jilau Khana. Edmonton, 2018. Digital Image.

- Gnawledge, and Uzman Almerabet. El Arte de Escuchar. Mp3. Vol. Granada Doaba. Spain: Gnawledge Records, 2009. freemusicarchive.org. http://freemusicarchive.org/music/Gnawledge/Granada_Doaba/14_El_Arte_de_Escuchar.

CITE

Keshani, Hussein (Researcher, Author, Voiceover, Audio Editor, Image Editor). “Multimedia: A Garden of Poems - Chahar Bagh Jilau Khana.” Evolving the Botanic Garden Project, July 31, 2017. .creative commons - Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Summary Legal

POEM 1

What is sukr (i.e. spiritual intoxication)?

To imagine the rose (gul) from the thorn,

To envision the invisible All (kull) from the part.

Farid al-Din Attar Nishapuri (Nishapur, Iran, d. 1221), Excerpt from The Book of Adversity (Musibatnameh). Translated by Maria Subtelney. 2007. (Original in Persian.)

Why Here?

Dozens of roses can be found in the Rose Bagh. The rose, which is mentioned in the poem, was frequently used in Islamic world poetry.

About this passage

The verse uses the rose and its thorns as an analogy to illustrate the unforeseeable nature of spiritual intoxication or enlightenment. Just as one who is unfamiliar with a rose can not imagine the beauty and fragrance of a rose's flower having only seen its sharp thorns, so too the hardships encountered by a spiritual seeker do not foretell the spiritual bliss at journey's end.

Attar's reference to part-whole relations (i.e. thorn-rose) shows that he, like many contemporary Arabic and Persian poets, were knowledgeable about ancient Greek philosophical debates on part-whole relations, an area of study now called Mereology (Varzi). Aristotle for instance argues a whole can be greater than its parts.

Attar was a pen name for Abū Ḥāmed Moḥammad b. Abī Bakr Ebrāhīm, a pharmacist and poet who was from Nishapur,Iran and was born around 540/1145-46. His most famous work was Conference of the Birds (Manṭeq al-ṭayr).

Like his other work, Attar's Book of Adversity (Musibatnameh) is an account of a troubled spiritual seeker who passes through 40 stages in search of a true guide. Angels, demons, celestial bodies, ancient prophets, metaphysical object, and the natural world including plants and animals are all sources of wisdom, culminating in a final encounter with the Universal Soul, who counsels him to abandon attachment to the self by looking within (Reinert).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Farid al-Din Attar Nishapuri (Nishapur, Iran, d. 1221). “Excerpt from Musibat-Nameh in Visionary Rose.” In Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovation and Cultural Change, 17. Washington, D.C.; [Boston: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection ; Distributed by Harvard University Press, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/228783948.

- Farid al-Din Attar Nishapuri (Nishapur, Iran, d. 1221). Musibat-Nama. Edited by Muhammad Reza Shafi`i-Kadkani. Tehran: Intisharat-i Sukhan, 1375. http://archive.org/details/MuseebatNama-AttarNishaburiFarsi.

- Farid̄-ad-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. Muṣībat-nāma-i Šaiyḫ Farīd ad-Dīn ʻAṭṭār Nīšābūrī. Edited by Nūrānī Wiṣāl. Tihrān: Intišārāt-i Kitābfurūšī-i Zuwwār, 1959. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/554295926.

- Subtelny, Maria E. “Visionary Rose: Metaphorical Interpretation of Horticultural Practice in Medieval Persian Mysticism.” In Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovation and Cultural Change, edited by Michel Conan and John Cress, 13–34. Washington, D.C.; [Boston]: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection ; Distributed by Harvard University Press, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/228783948.

- Wallace, Jeff. Aga Khan Garden - Rose Petal Fountain. 2018. Digital photograph. https://archnet.org/sites/16792/media_contents/134700.

- Mohamed Antar. A Solo Ney, n.d. https://soundcloud.com. https://soundcloud.com/ahmed-hisham-afifi/a-solo-ney-mohamed-antar.

POEM 2

One day when I ventured into the garden to regard its bloom,

My eyes beheld on a bower a withered rose.

When I inquired what had caused their blight,

“My lips for a moment opened in a smile in this garden,” it replied.

Lakhnavi, Ghalib (Lucknow, India, writ. 1855) and Abdullah Bilgrami (Lucknow, writ. 1871). Excerpt from The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. 2007. (Original in Urdu.)

About this passage

This passage appears at the beginning of a chapter in which the builder of the extraordinary garden, the Bagh-e Bedad, abducts the son of a man he has killed to hide a secret. While foreshadowing the story's events and conveying the garden's overwhelming beauty, the poem also hints at the spiritual danger of becoming enthralled with the material world and forgetting the hereafter.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Bilgrami, Abdullah, and Ghalib Lakhnavi. “Excerpt.” In The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Complete and Unabridged Translation, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi, 20. New York: Modern Library, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/883417767.

- Pritchett, Frances. “The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dastan-e-Amir Hamzah.” India International Centre Quarterly 19, no. 3 (1992): 27–47. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6015492798.

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - Withered Rose in the Rose Bagh . Edmonton, 2018. Digital Image.

POEM 3

[T]he rose is a memorial of the face of beautiful ones, {oh unknowing one / unknowingly};

the bird of the garden is a token/trace of some sweet-tongued one

Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir (Delhi, India, writ. 1751-2). Ghazal 128, 8. A Garden of Kashmir. Translated by Frances Pritchett. ca. 2013. (Original in Urdu.)

Original Text & Transliteration

گل یادگارِ چہرۂ خوباں ہے بے خبر

مرغِ چمن نشاں ہے کسو خوش زبان کا

gul yādgār-e chahrah-e ḳhūbāñ hai be-ḳhabar

murġh-e chaman nishāñ hai kisū ḳhvush-zabān kā

About this passage

In this couplet from a larger poem, or ghazal, the rose and the bird serve as unwitting reminders, if not embodiments, of beloved ones, perhaps long gone. Similar lines from other poets also allude to the cycle of life, how plants and animals die and provide nourishment to land and creatures only to be reborn.

The poet Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir (1723-1810), known simply as Mir, was a leading Urdu poet in the late-Mughal Delhi and Nawwabi Lucknow. He helped transform Urdu into a courtly and literary language rivalling, and eventually overtaking, Persian in South Asia (Russell and Islam). Though he wrote Persian poetry, he was a master of the Urdu ghazal genre. Ghazals are short poems typically composed of 7 to 12 rhyming couplets about unfulfilled religious and romantic longings. Originating in Arabia, the form became enormously popular throughout the Islamic world and was adapted to regional languages like Persian and Urdu.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir (Delhi, India, writ. 1165/1751-2). “Ghazal 128,8.” In A Garden of Kashmir, n.d.

- Pritchett, Frances. “A Garden of Kashmir: The Ghazals of Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir.” South Asia study resources compiled by Frances Pritchett, Columbia University. Accessed November 29, 2018. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00garden/index.html.

- Russell, Ralph, and Khurshidul Islam. “Mir: The Man and His Age.” In Three Mughal Poets: Mir, Sauda, Mir Hasan, 231–70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00garden/texts/txt_ralphrussell_1968.pdf.

POEM 1

@ the Chahar Bagh Mahtabi

All men and women are to each other

the limbs of a single body, each of us drawn

from life’s shimmering essence, God’s perfect pearl;

and when this life we share wounds one of us,

all share the hurt as if it were our own.

You, who will not feel another’s pain,

yo-u forfeit the right to be called human.

Saadi (d. 1184-1283/1291?). Selections from Saadi's Gulistan (Global Scholarly Publications). Translated by Richard J. Newman. (Original in Farsi.)

Why Here?

The grand vistas and shimmering water here invite deeper reflection about what is truly important in life, as this poem considers.

Original Text & Transliteration

بنى آدم اعضای یکدیگرند

که در آفرینش ز یک گوهرند

چو عضوى بدرد آورَد روزگار

دگر عضوها را نمانَد قرار

تو کز محنت دیگران بی غمی

نشاید که نامت نهند آدمی

banī ādam a'zā-ye yekdīgar-and

ke dar āfarīn-aš ze yek gowhar-and

čo 'ozvī be dard āvarad rūzgār

degar 'ozvhā-rā na-mānad qarār

to k-az mehnat-ē dīgarān bīqam-ī

na-šāyad ke nām-at nahand ādamī

About this passage

These famous lines, written by one of the most famous Persian poets in history, are from a work called the Rose Garden (Gulistan) by the poet Saadi (1184-1292), the pen name for Abū-Muhammad Muslih al-Dīn bin Abdallāh Shīrāzī. After visiting a garden with a friend, who collected flowers only to see them quickly die, Saadi resolved to create a literary garden mixing wit and wisdom that would last.

The poem is known as The Children of Adam (Bani Adam) and is advice he gives to an Arab king he encounters while offering prayers at the tomb of the Jewish/Christian prophet and saint John the Baptist, located in The Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria. Saadi was from Shiraz Iran, but was displaced with the Mongol conquests of Iran and travelled widely across Central Asia and the Middle East, studying for a time in Iraq.

The lines and are woven in gold thread into an elaborate carpet made by the contemporary master Mohammad Seirafian that was gifted by the Islamic Republic of Iran in 2005 to the United Nations in New York, where it now hangs. The lines are in the first ring surrounding the central medallion.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Saadi (d. 1184-1283/1291?). Selections from Saadi's Gulistan(Global Scholarly Publications). Translated by Richard J. Newman. Farsi.

- Garten, Mark. Photograph of UN Carpet by Mohammad Seirafian. New York, 2006. United Nations Collection, New York. Photo # 133991. https://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/133/0133991.html

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - Mahtabi. 2018.

- Gnawledge, and Uzman Almerabet. El Arte de Escuchar. Mp3. Vol. Granada Doaba. Spain: Gnawledge Records, 2009. freemusicarchive.org. http://freemusicarchive.org/music/Gnawledge/Granada_Doaba/14_El_Arte_de_Escuchar.

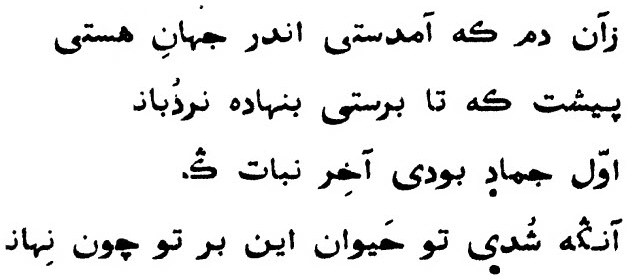

POEM 2

From the moment you came into the world of being,

A ladder was placed before you that you might escape.

First you were mineral, later you turned to plant,

Then you became animal: how should this be a secret to you ?

Afterwards you were made man, with knowledge, reason, faith ;

Behold the body, which is a portion of the dust-pit, how perfect it has grown! When you have travelled on from man, you will doubtless become an angel ;

After that you are done with this earth: your station is in heaven.

Pass again even from angelhood: enter that ocean ...

Rumi. XII, Selected Poems from the Divani Shamsi Tabriz, Edited and Translated by R. A. Nicholson, 1st published in 1898. (Original in Farsi.)

Original Text

About this passage

This often cited passage speaks of spiritual progression and the unity of creation. Mawlana Rumi was born in Central Asia and died in Konya, Turkey in 1273. Trained as theologian and legal scholar, he distinguished himself as a mystical poet.

The excerpt is from a work called the Diwan-i Kabir (The Great Collection) or the Diwan-i Shams-i Tabrizi (The Collection of Shams of Tabriz). Rumi composed these works following the spiritual transformation he underwent after meeting and training with his beloved teacher Shams of Tabriz, who sadly disappeared.

Rumi's works ranged from the contemplative to the erotic and were written mostly in Persian but also Arabic, Turkish and Greek, an indication of the multicultural environment in which he lived.

His actual name was Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī or Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Rumi. Rumi referred to the place he was from - Anatolia (i.e. modern Turkey) - which was known as Rome because it was formerly the seat of the Eastern Roman (i.e. Byzantine) empire (Nicholson, xv-li).

Today, his works have been translated into many languages, and he is one of the most popular poets in the English language.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Ǧalāl-ad-Dīn Rūmī. “XII.” In Selected Poems from the Dīvān-i Shams-i Tabrīz: Ed. and Transl. with an Introd., Notes and App., translated by Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, xv-li; 47. Cambridge: Univ. Press, 1898. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.52959/page/n3. Farsi and English.

POEM 1

@ the Ice Bagh

Be attentive, in the breeze’s folds there are messages,

and lean over, for the Ban trees at the foothill are leaning over.

They leaned over only to seek questions, while within them

a desire to speak about love, so converse with them and ask questions.

And convey secretly my love to the breeze, because

it is my rival when I am excited by the nightingales.

My question would be a consolation to the breeze,

while my tears for the way stations are flowing (sā‘il, also “questioning”).

"al-Sarhadi/al-Sarkhawi in Ibn Sa‘īd al-Andalusī, al-Muqtatʾaf min Azāhir al-Turaf (A Collection of the Flowers of Rarities) Andalusia/Aleppo, Syria, c. 685/1286. Translated by Samer Akkach. (Original in Arabic.)

Why Here?

In the Ice Bagh - wind often blows around mist, drawing attention, like the poem, to invisible breezes that may carry secret messages. Tall trees, though not Ban (i.e Moringa) trees, loom as if they are listening too.

About this passage

This poem belongs to a genre of landscape poetry in Medieval Arabic, which often used references to nature or the garden to explore the subtleties of romantic love and flirtation. Here the poet speaks of conversing with ban trees and of secret loves conveyed through the winds. The ban, or moringa, tree was known as the love tree and thought to exemplify the qualities of a beautiful woman (Davila, 110).

Ibn Said al-Andalusi or al-Maghrebi (1213-1286) was an anthologist, poet, historian and geographer, who was raised and educated in medieval Islamic Spain and later moved to the Middle East. On the advice of his friend, the son of the famous Ayyubid Sultan Salah al-Din, al-Maghrebi compiled an abridged collection of Arabic poetry called A Collection of the Flowers of Rarities (al-Muqtatʾaf min Azāhir al-Turaf), which this passage is from (Akkach).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Davila, Carl. Nūbat Ramal Al-Māya in Cultural Context: The Pen, the Voice, the Text. BRILL, 2015.

- Ibn Sa‘īd al-Andalusī, al-Muqtatʾaf min Azāhir al-Turaf (A Collection of the Flowers of Rarities) (Cairo: al-Hay’a al-Misriyya al-‘Āmma lil-Kitāb, 1984), 139. Andalusia/Aleppo, Syria, c. 685/1286. Translated by Samer Akkach. Samer Akkach, "Poetry and Landscape Aesthetics in the Arab-Islamic Tradition," http://web.mit.edu/akpia/www/articleakkach.pdf. Arabic.

- Kropp, Manfred. Zu Den Abschnitten Über Die Nichtklassische (Muwallad-) Dichtung Aus Dem Kitāb al-Muqtaṭaf Min Azāhir Aṭ-Ṭuraf Des Ibn Saʿīd al-Maġribī. Accessed June 22, 2019. https://www.academia.edu/29006028/Zu_den_Abschnitten_%C3%BCber_die_nichtklassische_muwallad-_Dichtung_aus_dem_Kit%C4%81b_al-Muqta%E1%B9%ADaf_min_az%C4%81hir_a%E1%B9%AD-%E1%B9%ADuraf_des_Ibn_Sa%CA%BF%C4%ABd_al-Ma%C4%A1rib%C4%AB.

- Pellat, Ch. ‘Ibn Saʿīd Al-Mag̲h̲ribī’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, P.J. Bearman (Volumes X, XI, XII), Th. Bianquis (Volumes X, XI, XII), et al. Accessed June 22, 2019. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3351.

- Nelson Byrd Woltz. Aga Khan Garden: The Ice Chabutra Spouts Mists of Water. Edmonton 2018. Digital Photograph. Nelson Byrd Woltz collection. https://archnet.org/sites/16792/media_contents/133040.

- Kaiho. Sitar Long, 2007. freesound.org. 37715__kaiho__sitar-long.aiff.

POEM 1

@ the SE Bustan

Fruit trees fill the eyes with abundance:

Quince, pear, apple, and pomegranites,

The golden kernels hung from the vine

Brew already in the vats of the drinkiers’ eyes

Peacocks preen on the promenades

And are a-swinging on the ledges.

Lakhnavi and Bilgrami, The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Translated by M.A. Farooqi. p. 18-19. (Original in Urdu.)

Why Here?

The SE Bustan is filled with fruit trees, much like the garden described in the passage.

About this passage

This passage is part of a poem that follows the amazement a emperor who has just seen the Bagh-e Bedad garden which his servantAlqash has built. In the The Adventures of Amir Hamza, the devious Alqash convinces the emperor to visit the luxurious garden (Bagh-e Bedad) that he built with ill-gotten wealth. Upon seeing the garden, the emperor marvels out loud at its beauty and at the exotic plants and abundant fruit it contains (Lakhnavi and Bilgrami, 18).

CREDITS

TEXTS- Bilgrami, Abdullah, and Ghalib Lakhnavi. “Excerpt.” In The Adventures of Amir Hamza, Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Complete and Unabridged Translation, translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi, 19. New York: Modern Library, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/883417767.

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - SE Bustan. 2018.

- Unknown. Imperial Palace Autumn Moon 《汉宫秋月》, n.d. The Internet Chinese Music Archive The Great Empire of China. https://www.ibiblio.org/chinese-music/MP3/TD03.Imperial_Palace_Autumn_Moon.mp3.

POEM 2

The man who plants bad seed hallucinates

if he expects sweet fruit at harvest time.

Saadi. Gulistan. Iran, 1258. Translated by Richard J. Newman, Selections from Saadi's Gulistan. (Original in Farsi.)

Why Here?

The SE Bustan is filled with fruit trees, and the passage makes reference to fruit orchards.

About this passage

Written by one of the most famous Persian poets in history Saadi (1184-1292), these lines are from the tenth story in the Rose Garden (Gulistan). After visiting a garden with a friend, who collected flowers only to see them quickly die, Saadi resolved to create a literary garden mixing wit and wisdom that would last.

They proceed the well-known extracted poem The Children of Adam (Bani Adam) and are part of his advice to be compassionate, which he gives to an Arab king he encounters while offering prayers at the tomb of the Jewish/Christian prophet and saint John the Baptist, located in The Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria. Saadi was from Shiraz Iran, but was displaced with the Mongol conquests of Iran and travelled widely across Central Asia and the Middle East, studying for a time in Iraq.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Saʻdī, and Richard Jeffrey Newman. Selections from Saadi’s Gulistan. New York: Global Scholarly Publications : International Society for Iranian Culture, 2004. 39. https://www.academia.edu/38078124/Selections_from_Saadis_Gulistan.

POEM 1

@ NW Bustan

The pageant of Nature is a fathomless ocean of beauty,

If eyes were to see every drop has in it tumultuous beauty.

Muhammad Iqbal (North India; England, writ. 1905-1924). Excerpt from Bāng-i Darā, Translated by Muhammad Iqbal, 1978. (Original in Urdu.)

Why Here?

From this viewpoint one can see the restored pond, the planted orchard, the built garden and forest in the background, a pageant of nature of sorts.

Original Text

محفلِ قدرت ہے، اک دریائے بے پایانِ حسن; آنکھ اگر دیکھے تو ہر قطرے میں ہے طوفانِ حسن

About this passage

These lines are from a poem found in a 1924 Urdu collection called Call of the Marching Bell (Bang-i Dara), by the famous philosopher-poet, lawyer and politician Muhammad Iqbal, who composed works in Persian, Urdu and English. The collection was written in South Asia and England and the poem speaks to Iqbal's love of Nature, as expression of the Divine. In these lines nature, like the Divine, is both fathomless and beautiful, with every element being a window into the larger whole.

A student of Arabic, English literature and philosophy, Iqbal studied in India and England where he became a barrister and then Germany. He would go on to be a major intellectual figure, who called for the establishment of the nation of Pakistan.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Iqbal, Muhammad. Bang-i Dara (Call of the Marching Bell). Lahore: Karimi Press, 1924. http://www.allamaiqbal.com/works/poetry/urdu/bang/text/index.htm.

- Iqbal, Muhammad. “Iqbal, the Poet of Nature.” Iqbal Review 18, no. 4 (January 1978). http://allamaiqbal.com/publications/journals/review/jan78/13.htm#_edn3.

- Keshani, Hussein. Aga Khan Garden - NW Bustan. 2018.

- Unknown. Sitar and Tabla Duo. Mp3. Vol. Field Recordings from India. India, 2008. freemusicarchive.org. https://archive.org/details/Field_Recordings_from_India-9888/Broos_-_45_-_sitar__tabla_duo.mp3.

POEM 2

Voices lifted high in singing,

Till the ape fell from the branches,

The flowing water stopped to listen,

The flying bird turned back to hear.

Unknown. Excerpt from Malim Deman. Translated by R. O. Winstedt. 1943. (Original in Malay.)

About this passage

The humorous passage belongs to the text Hikayat Malim Deman (The Epic of Malim Deman) a Malay tale of heroic adventure, based on a Malay tradition of oral adventure stories (cerita lipur lara) and South Asian and Middle Eastern influences. The Malay prince Malim Deman dreams a Muslim saint has told him to go upriver to find a wife among 7 fairy princesses who have descended to earth (Brakel-Papenhuyzen ). He marries, loses and regains his wife in fantastical adventure.

CREDITS

TEXTS- Brakel-Papenhuyzen, Clara. “Jaka Tarub, a Javanese Culture Hero?” Indonesia and the Malay World 34, no. 98 (March 1, 2006): 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639810600652352.

- Fang, Liaw Yock. A History of Classical Malay Literature. Institute of Southeast Asian, 2013.

- Sturrock, A. J., and Richard Winstedt. Hikayat Malim Deman. Methodist Publishing House, 1908

- Winstedt, R. O. “Nature in Malay Literature and Folk Verse.” J.R. Asiat. Soc. G.B. Irel. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 75, no. 1–2 (1943): 27–33.